A word used constantly that really bothers me is "conversate". I know it's correct but it really just grates on me. Just say "converse" for god's sake!!!

"conversate" is 200 year old slang that i never heard used until the 90s. i don't use it.A word used constantly that really bothers me is "conversate". I know it's correct but it really just grates on me. Just say "converse" for god's sake!!!

A word used constantly that really bothers me is "conversate". I know it's correct but it really just grates on me. Just say "converse" for god's sake!!!

A word used constantly that really bothers me is "conversate". I know it's correct but it really just grates on me. Just say "converse" for god's sake!!!

I also can’t stand those verbs that should obviously remain in noun form. I’m glad you opined that.You are correct, by the way. "Conversate" is a moronic fucking fake word. Fuck everyone who uses it!

I told you I was a selective English language purist.

I also can’t stand those verbs that should obviously remain in noun form. I’m glad you opined that.

Come again?“I’m really getting short of breath here!” he ejaculated.

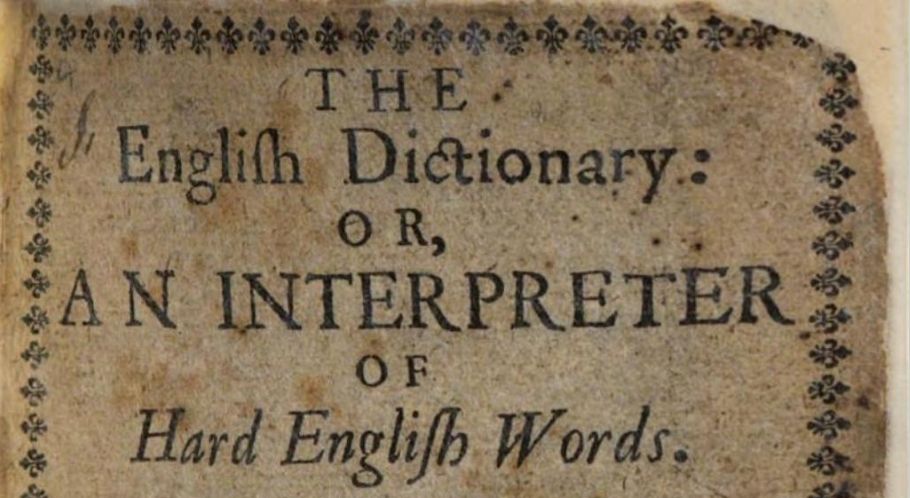

token (n.)

Old English tacen "sign, symbol, evidence, portent" (related to verb tæcan "show, explain, teach"), from Proto-Germanic *taikna- (source also of Old Saxon tekan, Old Norse teikn "zodiac sign, omen, token," Old Frisian tekan, Middle Dutch teken, Dutch teken, Old High German zeihhan, German zeichen, Gothic taikn "sign, token"), which is from from PIE root *deik- "to show," also "pronounce solemnly." Compare, from the same root, German zeigen "to show," Old English teon "to accuse,"

The meaning "coin-like piece of stamped metal" is recorded from 1590s. The older sense of "evidence" is retained in by the same token (mid-15c.), originally "introducing a corroborating circumstance" [OED, 1989].

token (adj.)

"nominal," 1915, from token (n.). In integration sense, attested by 1960.

also from 1915

chick (n.)

"the young of the domestic hen," also of some other birds, mid-14c., probably originally a shortening of chicken (n.).

Extended 14c. to human offspring, "person of tender years" (often in alliterative pairing chick and child) and thence used as a term of endearment. As modern slang for "young woman" it is recorded by 1927 (in "Elmer Gantry"), supposedly from African-American vernacular. In British use in this sense by c. 1940; popularized by Beatniks late 1950s (chicken in this sense is by 1860). Sometimes c. 1600-1900 chicken was taken as a plural, chick as a singular (compare child/children) for the domestic fowl.

also from mid-14c.

wait...i got my position only due to d.e.i????We do need more female representation here, don't we?

wait...i got my position only due to d.e.i????

Square-sail is attested by c. 1600. The nautical square-rigger is by 1829; square-rigged is from 1769. Square wheel as figurative of something that doesn't work as needed is by 1920.[T]he old square dance is an abortive attempt at conversation while engaged in walking certain mathematical figures over a limited area. [The Mask, March 1868]

Bitch goddess coined 1906 by William James; the original one was success.BITCH. A she dog, or doggess; the most offensive appellation that can be given to an English woman, even more provoking than that of whore. ["Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue," 1811]

Related: Bitchily; bitchiness.Mr. Ramsay says we would now call the old dogs "bitchy" in face. That is because the Englishmen have gone in for the wrong sort of forefaces in their dogs, beginning with the days when Meersbrook Bristles and his type swept the judges off their feet and whiskers and an exaggerated face were called for in other varieties of terriers besides the wire haired fox. [James Watson, "The Dog Book," New York, 1906]

Alle þe filþ of his magh ['maw'] salle breste out atte his fondament for drede. [ "Cursor Mundi," early 14c.]

The expression is related to, and may well derive from, an old joke. A man in a crowded bar needed to defecate but couldn't find a bathroom, so he went upstairs and used a hole in the floor. Returning, he found everyone had gone except the bartender, who was cowering behind the bar. When the man asked what had happened, the bartender replied, 'Where were you when the shit hit the fan?' [Hugh Rawson, "Wicked Words," 1989]

Then twenty-five of the best players in college were sent up to Brunswick to combat with the Rutgers boys. Their peculiar way of playing this game proved to Princeton an insurmountable difficulty; .... Two weeks later Rutgers sent down the same twenty-five, and on the Princeton grounds, November 13th, Nassau played her game; the result was joyous, and entirely obliterated the stigma of the previous defeat. ["Typical Forms of '71" by the Princeton University Class of '72, 1869]